Overview and Description

The discussion of disparate health outcomes is relevant to all practices of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. It is essential that all patients fully benefit from the consultative guidance and interventions of Physiatry. Yet it is evident that our field is not immune to personal, institutional, or systemic realities that bias care against key groups within our patient populations. Thus, we must appreciate the literature on the topic and actively plan mitigation strategies to ensure the best outcome for all patients under our care regardless of setting or area of focus. This submission reviews the state of access to and outcomes from rehabilitation services through the lens of equity.

Individuals with disabilities are already marginalized. However, the additional lens of socio-economic status, gender, religion, race, and culture further disenfranchises persons from the privilege of those in the majority. This article focuses on race and culture, a challenging topic that elicits a strong emotional reaction from those to whom the centering of bias and exclusion may seem novel or irrelevant. It is also triggering to those who have personally experienced intentional or incidental disempowerment. However, this complex work is critical to our future as a field and to the health of our patients.

There are two major components of disparate outcomes for patients receiving rehabilitation services which influence one another: (1) disparate treatment of marginalized patients and (2) a lack of diversity in the PM&R workforce. Firstly, different assessment/treatments of those marginalized result in outcomes are not driven exclusively by best practices. Examples of racial and ethnic disparities in rehabilitation outcomes are well documented:

- A review of racial and ethnic health disparities done through the Department of Veterans Affairs prefaced a report on this issue as “the most serious and shameful health care issue of our time.”1

- There is reduced healthcare utilization and access for Hispanics in the United States.2

- There are poorer functional outcomes for American Indian/Alaskan Native Children receiving inpatient rehabilitation.3

- Black adults with TBI had lower cognitive, motor, and total functionality at discharge than non-Hispanic white adults.4

- Black adults and children are less likely to receive analgesia for acute pain.5,6

- Black and Latinx adult and pediatric patients were less likely to be discharged from acute care hospitals to rehabilitation centers than white patients following significant brain injury.7,8

Second, a significant factor impacting racial and ethnic health disparities is the lack of diversity in the rehabilitation work environment. Black and Latinx physicians are even more under-represented in academic medicine at all ranks and in all specialties (including PM&R) in 2016 than in 1990.9 From 2007 to 2018, the composition of Black PM&R full professors declined from an abysmal 2.5% down to 0.8%.10

The data is equally grim for rehabilitation-related allied health professionals in physical therapy,11 occupational therapy,12 and speech-language pathology.13 Thus, the profound lack of diversity in physical medicine treatment staff is discordant with the composition of racial and ethnic groups in the larger population. That lack of representation is not only ethically troubling and harmful to patients, but it can cause financial and operational challenges for clinical practices. Healthcare disparities are a barrier to optimal metrics in performance-based reimbursement models for consultants, inpatient providers, and outpatient providers across all patient age groups. It is imperative to reverse the reality inferred by overwhelming data that the race/ethnicity of the patient determines Physiatric outcomes.

Relevance to Clinical Practice

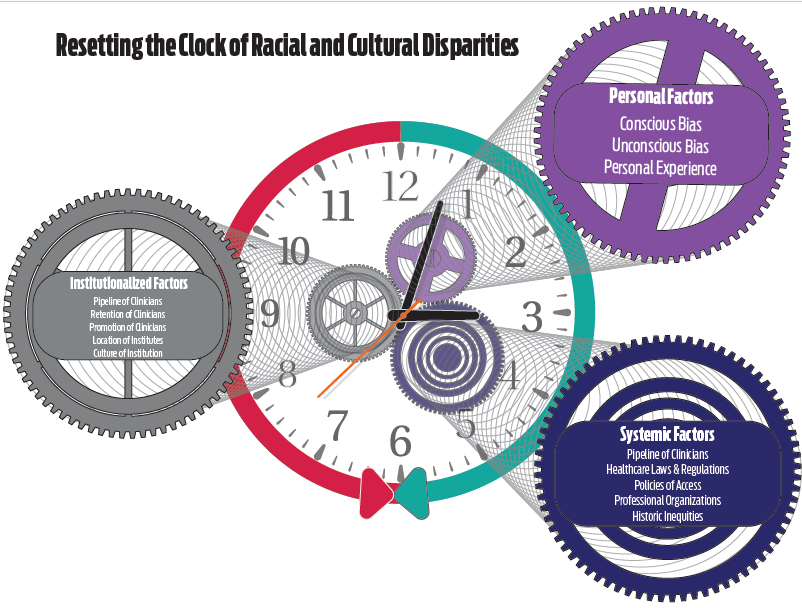

The need for equitable racial and ethnic outcomes for patients under the rehabilitation umbrella is crucial to a physiatric practice. Change requires approaches that move from micro to macro: targeting individual behavior, institutional factors, and systemic challenges. Schematically, this is represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Resetting the Clock of Racial and Cultural Disparities

Legend: The green arrow represents the evolution of societal thought. It advances the clock towards the future as mores and norms evolve (clockwise rotation). The red arrow represents resistance to change. This is the force opposing modification created by the inertia of accepted or typical convention or societal order. This slows or retards the advancement toward a new normal (counterclockwise rotation). The gears inside of the clock are the components that make the clock function. They are factors that contribute to worsening or amelioration of the disparities. (Created May 2020, A. Kenyatta Parks & Maurice Sholas)

Starting at the most granular level, individual clinicians must be aware of their biases and practice culturally competent care. It will inform the overall quality with which patients are managed, and it serves as a proxy for provider competence. Few, if any, providers believe that they treat their patients differently or below the standard of care. However, the data show that this assumption is not true. Belief in goodness or intent is not an exemption from the consequences of disparate health outcomes, and a concerted effort to shift these tides is overdue.

At a larger level, those individual physicians and providers are part of a community. Diverse and equity-oriented communities matter. Data shows that more racially diverse staff have better financial outcomes14 and have a more positive impact on patient trust and clinical outcomes.15 Patients experiencing racism in a health care setting “…had 2-3 times the odds of reporting reduced trust in healthcare systems and professionals, lower satisfaction with health services and perceived quality of care, and compromised communication and relationships with care providers.”16 These factors underscore the impact of the individual provider and the community of care on the patient experience.

Examples of institutional or structural bias can be reflected in more unexpected ways. A facility whose location is not easily accessible via public transportation represents structural bias that could negatively affect marginalized populations. Another example is when a care organization has an unstated preference for private insurance or limits the number of patients on public insurance accepted for services. This phenomenon was demonstrated clearly when offices of orthopedic surgeons were called with a fictitious patient having a meniscal tear. Medicaid patients were more likely to be denied an appointment and waited longer for one when it was granted.17 These decisions seem purely operational at first glance but reduce access for marginalized racial and ethnic groups, specifically Black and Latinx patients who are less likely to have commercial insurance.18

Structural factors also include the work environment for providers of color and how well they are recruited, retained, and promoted. Like the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 codified the aspirations of inclusion for the patients that physiatrists treat in the United States, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 codified federal rules against discrimination in the United States based on race, color, religion, national origin, or sex. However, this prohibition has been less effective against the microaggressions and biases that harm physiatrists of color19 and secondarily on the patients said providers serve. The Oakland Men’s Health Disparities Study showed that having a black doctor decreased the black-white gap in cardiovascular mortality by 19%.20 Similarly, having a racially diverse Physiatry workforce has the potential to be a powerful counter to the disparities demonstrated in this review affecting minority patients. Culturally competent care matters. To improve racial healthcare disparities, work environments that are affirming and inclusive for minorities are crucial. Negative institutional factors must be addressed and mitigated with intentionality.

On an even larger systemic level, there has been an increased focus on health disparities in professional organizations representing the diaspora of medical services. In response to the increasing demands of community affinity groups and lagging minority membership, the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation founded a diversity and inclusion task force in 2019, resulting in a strategic plan with a three-year arc. The American Medical Association, the American Hospital Association, and the American Association of Medical Colleges (organizations with a history of being exclusively the province of white males) have all appointed senior-level leaders titled Chief Diversity Officers. In 2008, the American Medical Association specifically and formally apologized to black doctors for a legacy of exclusion dating back to 1870. It is unclear if these changes represent simply an agreement in principle that issues related to racial disparities are important or if these initiatives will translate into recruiting and retaining diverse physicians and administrators who elicit tangible changes.

Finally, the micro to macro-level changes that improve diversity in clinical practice requires modification of training programs and pathways. There is a clear role for education along the entire continuum of medical training and maintenance of continuing education. Insertion of medical ethics and humanities into the formal process of medical education at the pre-medical school level, medical school curriculum, post-graduate training years, and in practice is a proposed way to make physicians better able to recognize injustice and health inequity in the system.21 They can then use their power and privilege to overcome and reverse those findings.21 The composition of PM&R Residency Training programs is key as well. Data from the 2014/5 to the 2019/20 PM&R Residency Match cycles demonstrated an “…underrepresentation of women and multiple racial and ethnic minority groups in the field…”.25 This is cautionary data that the divergence between the professionals in the field and the patients being served could grow without improved recruitment and retention efforts. It is the responsibility of the individual physiatrists, the systems within which they work, and the professional organizations supporting the House of Medicine to address racial health disparities in a multifactorial way. At the individual level, the benefits of equitable health outcomes are obvious. At the institutional level, the benefit lies in improved revenue stream and performance metrics. At the systemic level, this makes the professional and clinical staff more concordant with the racial and ethnic make-up of the populations they serve.

Cutting Edge/ Unique Concepts/ Emerging Issues

Unconscious and often snap decisions people make about others are called implicit bias and, while not intentional, contribute to health disparities.22 These biases influence a physiatrist’s response to a person, their medical complaint, and their perceived compliance with treatment recommendations. The degree to which a person has implicit biases against a given group is measured via the Implicit Association Test (IAT).23 Two key criticisms of this approach are that IAT results are not always coupled with training on how to make durable changes to those biases, and naming a bias unconscious minimizes the responsibility a given person has to actively combat it. A more lasting approach to change is for individuals and organizations to partner with existing social justice and equity organizations to craft best practice opportunities. In addition to groups like the National Medical Association, National Hispanic Medical Association, and the Association of American Indian Physicians, rehabilitation practitioners can partner with local students, trainees, and provider affinity groups. That adds a diversity of voices and perspectives to the practice of medicine as individual practice requirements and institutional standards are created. Organizations with larger societal equity focuses also have divisions dedicated to health equity such as The National Urban League, Unidos, and the Color of Change. In making change, physical medicine practitioners do not have to reinvent decades of validated interventions and approaches to equity. Partnership is a path forward.

Gaps in Knowledge/ Evidence Base

Systematically tackling race/ethnic biases is challenging. In a survey-based exploration of Latinx patient experience following strokes, Lisabeth et al. partnered with inpatient rehab facilities, skilled nursing facilities, home health agencies, and outpatient rehabilitation providers.24 Initially, 80% of the community partners agreed to return the questionnaire data. Ultimately, only 12% did so. The reasons for this may be multifactorial, but the reticence to report a reality perceived as negative or shameful is a barrier to understanding and addressing racial health disparities. Making progress and decreasing racial and ethnic disparities requires intersectionality and it necessitates that the burden of change not be exclusively laid on those affected. As providers that care for adults and children with physical disabilities, we are trained to advocate for groups of marginalized persons. This same advocacy must also be applied to deconstructing barriers to equitable health outcomes for those additionally marginalized by race and ethnicity. Change requires courage that persists in spite of the many factors that resist it and a consistency that overcomes our history.

References

- Peterson, K. et al. Mortality disparities in racial/ethnic minority groups in the veterans health administration: an evidence review and map. Am. J. Public Health 108, e1–e11 (2018).

- Flores, L. E., Verduzco-Gutierrez, M., Molinares, D. & Silver, J. K. Disparities in health care for hispanic patients in physical medicine and rehabilitation in the united states: A narrative review. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 99, 338–347 (2020).

- Fuentes, M. M., Bjornson, K., Christensen, A., Harmon, R. & Apkon, S. D. Disparities in Functional Outcomes during Inpatient Rehabilitation between American Indian/Alaska Native and White Children. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 27, 1080–1096 (2016).

- Warren, K. L. & García, J. J. Centering race/ethnicity: Differences in traumatic brain injury inpatient rehabilitation outcomes. PM R 14, 1430–1438 (2022).

- Lee, P. et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the management of acute pain in US emergency departments: Meta-analysis and systematic review. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 37, 1770–1777 (2019).

- Wing, E., Saadat, S., Bhargava, R., Yun, H. & Chakravarthy, B. Racial disparities in opioid prescriptions for fractures in the pediatric population. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 51, 210–213 (2022).

- Gorman, E. et al. Is trauma center designation associated with disparities in discharge to rehabilitation centers among elderly patients with Traumatic Brain Injury? Am. J. Surg. 219, 587–591 (2020).

- Shah, A. A. et al. Gaps in access to comprehensive rehabilitation following traumatic injuries in children: A nationwide examination. J. Pediatr. Surg. 54, 2369–2374 (2019).

- Lett, E., Orji, W. U. & Sebro, R. Declining racial and ethnic representation in clinical academic medicine: A longitudinal study of 16 US medical specialties. PLoS ONE 13, e0207274 (2018).

- Zhang, Y. et al. Physical medicine and rehabilitation faculty diversity trends by sex, race, and ethnicity, 2007 to 2018 in the united states. PM R 13, 994–1004 (2021).

- Data USA. Physical Therapists. https://datausa.io/profile/soc/physical-therapists (2022).

- Data USA. Occupational Therapists. https://datausa.io/profile/soc/occupational-therapists (2022).

- Data USA. Speech Language Pathologists. https://datausa.io/profile/soc/speechlanguage-pathologists (2022).

- Hunt, V., Layton, D. & Prince, S. Why diversity matters. McKinsey & Company (2015).

- Sederstrom, N., Sholas, M., Haredman, R., Nauetz, S. & Wu, J. Presentation. The Color of Medicine: Confronting the Problem of Racism in Clinical Settings. (2018).

- Ben, J., Cormack, D., Harris, R. & Paradies, Y. Racism and health service utilisation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 12, e0189900 (2017).

- Wiznia, D. H. et al. The influence of medical insurance on patient access to orthopaedic surgery sports medicine appointments under the affordable care act. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 5, 2325967117714140 (2017).

- Sohn, H. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Insurance Coverage: Dynamics of Gaining and Losing Coverage over the Life-Course. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 36, 181–201 (2017).

- Overland, M. K. et al. Microaggressions in clinical training and practice. PM R 11, 1004–1012 (2019).

- Alsan, M., Garrick, O. & Graziani, G. Does Diversity Matter for Health? Experimental Evidence from Oakland. American Economic Review 109, 4071–4111 (2019).

- Doukas, D. J. et al. Transforming educational accountability in medical ethics and humanities education toward professionalism. Acad. Med. 90, 738–743 (2015).

- Zestcott, C. A., Blair, I. V. & Stone, J. Examining the presence, consequences, and reduction of implicit bias in health care: A narrative review. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 19, 528–542 (2016).

- Greenwald, A., McGhee, D. & Schwartz, J. Measuring Individual Differences in Implicit Cognition: The Implicit Association Test. Journal of Personality and Soclal Psychology 74, 1464–1480 (1998).

- Lisabeth, L. D. et al. The difficulty of studying race-ethnic stroke rehabilitation disparities in a community. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 25, 393–396 (2018).

- Dixon G. et al. Trends in Gender, Race and Ethnic Diversity Among Prospective Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Physicians. PMR. In Press. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmrj.12970 (2023).

Original Version of the Topic

Maurice G. Sholas, MD, PhD. Racial Disparities in Access to and Outcomes from Rehabilitation Services. 7/17/2020

Author Disclosure

Jennifer Bond, BS

Sholas Medical Consulting, LLC, Consulting Remuneration, Program Operations Professional

Maurice G. Sholas, MD, PhD

Sholas Medical Consulting, LLC, Employment, Owner

NS Pharma, Honorarium, Speakers Bureau

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Grant, Clinical Fellow